As the NFL is prepared to crown a champion Sunday night during Super Bowl LVI in Los Angeles, it is mired in a lawsuit over equal representation in the coaching ranks. There is a dearth of Black coaches, while African-Americans make up about 70% of NFL players.

There was a time when Black people were kept out of the league altogether — until four men changed the face of the game.

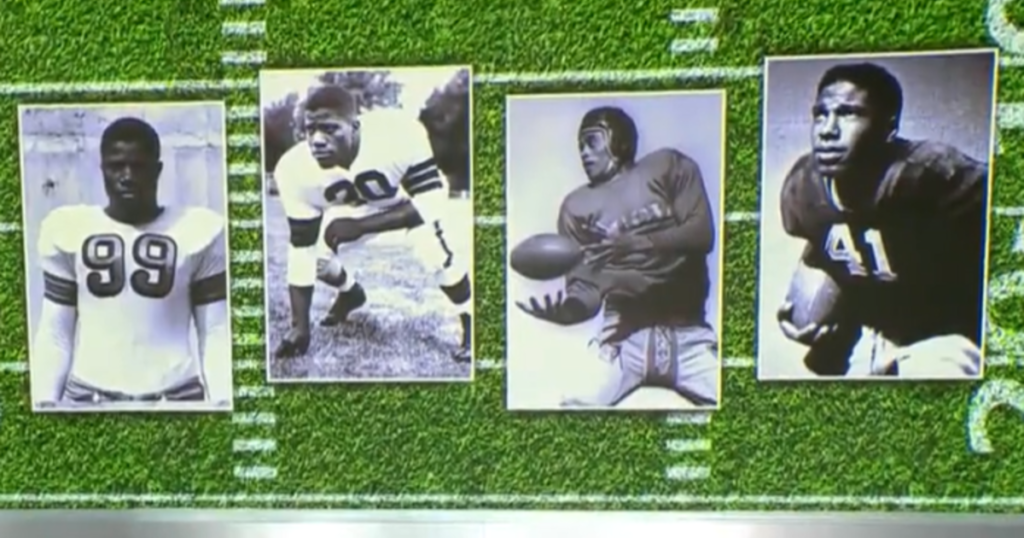

That long-forgotten part of the NFL’s history is the subject of a new book, “The Forgotten First,” which looks at the lives of Kenny Washington, Woody Strode, Marion Motley and Bill Willis. Former NFL player Keyshawn Johnson and award-winning NFL columnist Bob Glauber co-wrote the book to tell the story of the four men, who broke the NFL’s color barrier.

Despite being an integrated league at its founding, there were no Black players in the NFL from 1933-1945.

“There was basically a gentleman’s agreement that there would be not Black players in the NFL,” Glauber told CBS News’ Dana Jacobson. “Washington’s owner, George Preston Marshall, probably expressed it most outwardly that he did not want Black players on his team. … Other owners went along with it.”

That changed when the Cleveland Rams decided to move to Los Angeles and wanted to use the publicly funded Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. L.A. sports journalist, Halley Harding, a former athlete, led the charge to integrate the team.

“They felt, oh, this was just gonna be rubberstamped. Yeah, great. Rams wants to move to L.A., play in the coliseum. Sure, go ahead. But Harding and several of his colleagues said, ‘No.’

“This is after the war now, and there had been a push to get African Americans in baseball and in football during the war,” said Glauber. “Black men are fighting alongside White men to defeat Hitler and the Japanese empire. Why shouldn’t they have the fairness of opportunity at home.”

“So Halley Harding made that point in a very emotional speech to the coliseum commission.”

In 1946, one year before Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier, his former teammate, Kenny Washington, was signed by the Rams. He soon pushed the team to sign another UCLA teammate: Woody Strode.

Around that same time, the NFL’s rival league, the AAFC, would also integrate with Ohio coaching great Paul Brown, signing two Black players — Marion Motley and Bill Willis — to his 1946 Cleveland Browns squad.

Brown would later say he wasn’t looking to make civil rights history by adding the \players to the team.

“He did it because he wanted good football players. … There was other owners prior to that that wanted to do it, but they just didn’t want to upset the other owners. They wanted to. He realized that, he was like, ‘Yeah, I got to have me something that’s gonna help me win,” Johnson said.

The pair won four straight AAFC championships in Cleveland on their way to hall of fame careers. In L.A., Washington played just three seasons with the Rams before injury and age forced his retirement. Strode only played one, but he stayed in Hollywood to act.

The book shares a previously unpublished interview from Strode where he lamented integrating the NFL was the low point of his life.

“There was an instance in the first year of the Cleveland Browns where Paul Brown kept Willis and Motley home for a game in Miami because they received death threats,” said Glauber.

“The opponents sticking razor blades in their gloves, like in their tape, trying to slice them up. Stepping on them with their cleats, who does that?” Johnson said.

But the four men faced the challenges, and kept playing.

“I would say first of all, it’s heart and guts, perseverance. I couldn’t do it. But it says a lot about them to be able to do what I would call something for the greater good. You can’t tell the story of the National Football League without telling the story of these four men,” Johnson said.

None of the forgotten first are still alive, but family members of the men will be recognized at the Super Bowl on Sunday, and the L.A. City Council has declared Sunday “Kenny Washington Day.”